The Federal Reserve voted Wednesday to cut interest rates, but the unusually narrow margin revealed deepening divisions within the central bank as it attempts to navigate rising inflation, slowing hiring, and the economic uncertainty triggered by global tariff pressures. In a 9–3 vote, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) lowered its benchmark rate to a range of 3.5% to 3.75%—a modest 0.25-point cut that left neither hawks nor doves fully satisfied.

The split vote was far from typical for the Fed, which usually strives for near-unanimous agreement. Fed board member Stephen Miran pushed for a steeper cut of 0.5 percentage points, signaling urgency about weakening economic conditions. Meanwhile, Chicago Fed President Austan Goolsbee and Kansas City Fed President Jeffrey Schmid voted against any rate cut at all, arguing that inflation remains too high to justify easing monetary policy.

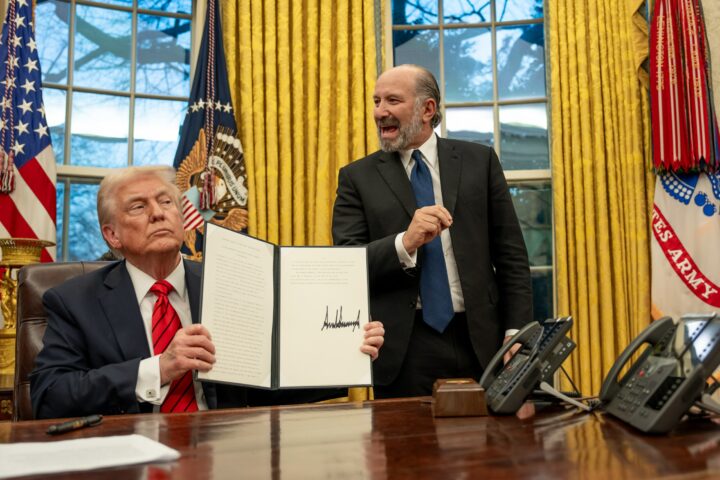

The dissents highlight the challenge facing Fed Chair Jerome Powell as he attempts to hold together a fracturing committee at a moment when the economy appears to be at an inflection point. The internal tensions could soon become someone else’s problem: President Trump is expected to name Powell’s successor in the coming days or weeks, a decision that will shape the direction of U.S. monetary policy for years to come.

Fed officials have been debating how aggressively they can cut rates without undermining efforts to keep inflation in check. After falling sharply during the final year of the Biden administration, inflation picked back up after Trump took office and imposed billions in tariffs, putting upward pressure on prices. At the same time, hiring has slowed sharply, unemployment has risen, and consumer confidence has faltered—adding urgency for those who argue rate cuts are needed now to stabilize the economy.

While dissenting votes on interest rate decisions are not unheard of, three votes against the majority is a significant departure from normal Fed procedure. The last time it happened was in 2019, when the Fed cut rates to undo previous hikes aimed at containing inflation that ultimately never emerged.

This time, however, inflation concerns are real. Several Fed officials remain wary of easing too quickly with inflation still above the central bank’s 2% target. They point to the Fed’s sluggish response to the post-pandemic inflation spike as a warning against acting too cautiously now.

But others on the FOMC view the current inflation pressures as largely temporary and driven in part by tariff policy—not by overheating economic fundamentals. According to minutes from the committee’s October meeting, this group believes deeper cuts might be necessary to prevent the slowdown from becoming a more serious downturn, especially as wage growth cools and job losses mount.

Complicating matters further is the lack of reliable federal data for October. The government shutdown shuttered the Bureau of Labor Statistics that month, halting the collection of employment and consumer price data. With critical reports missing, policymakers have been forced to make decisions with less clarity than usual—yet another factor contributing to the discord among Fed officials.

The narrow vote and stark disagreements underscore just how delicate the economic balancing act has become. Whether the Fed can maintain unity—and whether the next chair can calm the storm—remains an open question as the economy faces mounting pressures on multiple fronts.

[READ MORE: New Poll Shows Buttigieg Struggling Badly With Black Voters, Far Behind Leading Democrats]